ABS Magazine interview with Chad Kassem of Acoustic Sounds

|

Chad Kassem and Acoustic Sounds

"I Always Did Like Music More Than the Average Next Guy.” Scott M. Bock |

|

Chad Kassem has been leading surprising music industry trends since the late '80s. He got his start with LPs - never giving up on the special sound he heard when he played records. Today, Kassem is often credited with their resurgence. Audiophiles and a new generation of music fans are keeping Kassem busy recording, re-releasing, and selling vinyl. In the past few years, he has also led the market on high resolution downloads [HiRez] of music for audiophiles who want quality sound using a computer. |

|

| Meanwhile, Kassem has been supporting blues music and musicians from his native Louisiana out of deep love for both the music and the artists, no matter whether their recordings sell. He often says, 'I make money selling records and I spend it making them and putting on my concerts'. In fact, most of the original recordings Kassem has made over the years are of blues artists that he feels have to be heard. Kassem's booming voice and his thick Louisiana drawl easily precede him as he walks through one of his oversized Acoustic Sounds buildings in his adopted hometown, Salina, Kansas. He wears jeans, running shoes, and a grey sweatshirt with his APO logo, and he is always on the phone. He leans down to pick up a stray item from the floor and signals with his hand to respond to a question. His growing number of employees marvel at his energy, guts, and his ability to get things done. Kassem's love for records led him into the audiophile equipment business to serve customers who bought records from him. And, he has continued to expand his reach with his own high end recording studio, a record label, a record pressing plant, and the high resolution music downloads. He says has more than 7,000 records at home and at least another 7,000 from his collection in a concrete vault in his office building. |

|

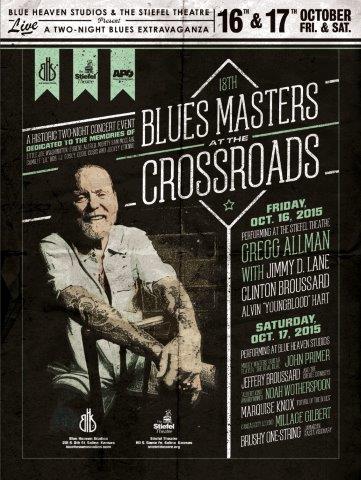

| Kassem established an annual music festival that will reach its 19th year in 2016. Blues Masters at the Crossroads has featured top notch bluesman and women – well known and many unknown during its long tenure. Kassem is now releasing the music from these concerts through downloads that have a remarkable sound quality. He is also preparing to sell quality video of these shows. No business school graduate – Kassem is in fact, a former short order cook who did not attended college. The lack of formal training has never been a problem. He is candid that his love for music coupled with his tough early years when he was using and buying and selling drugs, translated directly into success as a music mogul who listens to records and buys and sells them. He has been sober now for more than 30 years - drinking soda while out listening to music. He is married with a young daughter who comes to dance in the aisles at Blues Masters. Kassem is clearly a man on a mission focused on the quality of his product, treating his customers well, and, in many cases, giving them something they cannot get anywhere else. All these years in the business have not dampened his enthusiasm. He is well known for sitting friends down in front of a turntable to demonstrate the sound quality of records he has recorded or of LPs he discovered years ago. And, he will talk for hours about his favorite artists – especially Lightnin' Hopkins and Clifton Chenier. Kassem and his various businesses – Acoustic Sounds, Analogue Productions, Blue Heaven Studios – now has control of all aspects of music. He says that is important because he wants the sound just right. |

|

|

He and Acoustic Sounds have been featured regularly on television, in print, and on the radio. There is a fascination with the man and also with his commitment to blues and the return to vinyl. His 2015 purchase of decade old record pressing equipment that had been dormant for decades hit a chord with the press and spiked interest in Acoustic Sounds. Today, his warehouse, showroom, offices, and printing plant in Salina are visited by people from all over the world. He offers tours during his Blues Masters weekend and sticks it out for jam sessions that often run all night.

"I was born in Lafayette, Louisiana. Growing up, music was just around. It had to rub off. Like, Warren Storm and G.G. Shinn and them, we just thought those were bar bands. We just thought they were cover bands. But, actually, those guys were making records. |

|

| When I was a kid, you could sneak into clubs. They didn't care back then in Louisiana. You could buy beer when you were ten years old. You could hear Zydeco anywhere. It was everywhere. You almost got to a point where you didn't appreciate it at all. You took it for granted. Growing up in Lafayette, you didn't realize that other cities didn't have these swamp pop bands and didn't have Zydeco. My father was a strict disciplinarian. So, the first ten years of my life he was like on me and I had to be good and learn sports and all that which I still love. But, right when I started getting high, he quit teaching football and he opened up a clothing store right around the time of Super Fly and Shaft and all that. So, he started getting high around the same time as me [laughs]. He went from being the most strict disciplinarian to being cool. We were both getting high – not at the same time – not with each other. Then he opened this Black clothing store. I mean, when you went to the store there was platform shoes, hats, and Shaft was on or Me and Mrs. Jones. So, I really got a good dose of the soul music of the time – back when all that shit was hitting. I mean the O'Jays, the Temptations, the Four Tops - and we loved it. And, then there were a lot of concerts – Michael Jackson - B.B. King would always be playing. Back then, almost all of us had a [stereo] and a hundred albums instead of the computer - and it was fun. So, I had that - and we always loved that – all of my friends. So, when I came to Salina [Kansas] at 21 to get sober, I asked my dad to bring up my system. This would be about '84. So, he brought my stereo and a hundred albums and most of them were scratched from partying. I started replacing some of my favorite albums. I always did really like music more than the average next guy. |

|

| I went back to Lafayette - and I went to see my old friend Chet Nixon. This was right when CDs were coming out. And, he pulled out these special albums – these are original master recordings and these half speed master audiophile albums. And, I said, 'I got a bunch of those and they ain't any better than any regular albums. I bought some and I don't notice any difference'. And, he's like, 'There's a subtle difference'. I was expecting something to just come out of the speaker and just slap me about the face. And, I didn't hear that. So, he goes, 'You got to sit down in between these two speakers and just listen'. He said, 'I'm going to explain what to listen for – you got to be quiet. Sit in the middle and just concentrate for one song. That's all I'm asking you to do. Listen – there are no ticks and pops. And listen to how clear it is. Just shut up for one song'. That was hard to do. But, I gave him that. And, I was like, 'Wow, man'. I appreciated the subtle differences. It just blew me away. 'That's some serious sound, man'. So, he started showing me different audiophile records that had been reissued. And, he said, 'This one right here is worth $100. This one's worth $50. Nobody can find them because they're all out of print'. So, when I went back to Salina I went to a record store and they had about 300 of them and a lot of ones that were very, very valuable. First, I helped Chet buy them but then I thought, 'Shoot, I should start buying them.' It was Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, Nautilus Half Speeds, some direct to disc like Sheffield Labs. And, a lot of them would be reissuing pop records. So, what I would do – I would buy, sell, and trade. So, I would look for them. I'd go to every town and I'd buy two's and three's of them. I'd keep one and have one for a back-up and use some to trade or sell. And I got really, really passionate about this. I couldn't wait to go back home to Lafayette to go to every record store and find some – go to New Orleans. This was still in '84, '85. I was working as a cook for little more than minimum wage. I was just trying to build my collection. I was in a halfway house. When I started serious collecting I was just getting out [of the halfway house]. Back when I asked my dad to bring me my records, I was still in the halfway house. But, I was only there for six or seven months. By the time I got out, I would go to Kansas City or Wichita and I would look for records. I got to Kmart and there's a cut-out bin and they'd have a bunch of cut-out records and every now and then they would have a half speed master in there. So, I asked the lady at the store and she says, 'Every Tuesday, a guy comes in and he stocks them. He fills the bins'. So, I went there and I waited for him. So, he came and I said [to him], 'See these particular records. I really love these'. He says, 'I buy them from this wholesale company in St. Louis'. He gave me the phone number. And, I talked to the owner on the phone and they had a list and it was like 100 different master recordings from .50 to $5.00 each, which was just a bargain. |

|

| I had hit the mother lode. So, I started buying records directly from them. Then, I find another company that was doing it, and then more companies. Boom, that was the start. I started bringing records to the restaurant. I'd bring a box out of my truck and sell them to the other employees. I finally put a little ad in the back of Audio Magazine and that's what really started [my career]. I was maybe 25, 26. My whole apartment was so full of albums you couldn't walk in it. I started making a lot more money. I'm thinking maybe I ought to quit my job because I'm making more money and it's starting to cost me money to go to work. I did both as long as I could until I was making three times the money [selling records]. Then, I still wondered if I should do both. I'm not real religious and I didn't want to be lazy - one night I prayed about what to do. I guess I got my answer. Between '85 and '88, I lived in that apartment selling records from there. By '88, I was able to buy a ranch style house. By '91, I was doing $100,000 a month. The City got upset. Everything was cool until the 18 wheelers started pulling in [laughs]. Then the City wanted me to move. When CDs came out, I trusted my ears. I liked CDs alright. But, I never was that surprised that vinyl kept doing better and better. What really surprised me was CDs dying like it did. I never saw that coming. But, I never thought that LPs would die. So, by '88 I had too many records and I had to move out of the apartment. From '88 to '91, I was doing it out of a ranch style house with up to eleven people helping me. And, then they made me move. I moved downtown. Then, I out grew that and bought a building and we were there for ten years. That was from '94 to 2004. And, I had started selling stereo equipment probably around 1990. And, then I bought an old grocery store from about 2004 to 2011. And then we moved to where we are now. I never went to college. I really learned how to wheel and deal from selling dope. It's just buy, sell, and trade – that's all it is. I sold dope so I could have more dope, so I could support my habit. I sold records so I had more records to support my record collecting. I've been sober since February of '84. |

|

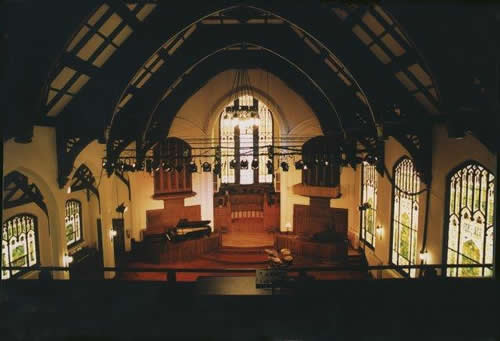

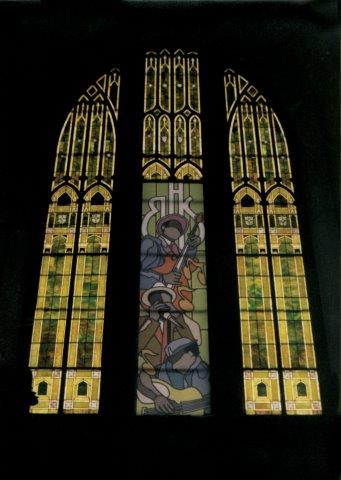

| I have a good ear but - it's funny but I never learned to play an instrument. When I was a kid and my guitar teacher would come over, the bar chords would frustrate me. I'd get him stoned and I'd tell him what songs I wanted him to play. So, he'd be entertaining me [laughs]. By 1990 there was barely any new vinyl. And, the rare collectable stuff was hard to get. So, I started reissuing vinyl and by that time I was really getting deeper into blues. I did jazz, classical, and pop but I also reissued blues. So by '91 we were reissuing records through Acoustic Sounds' Analogue Productions. We were remastering on 180 gram premium vinyl. You could hear how good it sounded. So, I thought, 'I'll reissue some blues. Then I thought, let's record some blues.' And that's when we did Bluebird [Jimmy Rogers] in '94. I recorded that in Chicago. Bluebird won the [1995] W.C. Handy Traditional Blues Album [of the Year] award. Then, I bought the [Blue Heaven] church in Salina in'96. I thought about living there. It was built in 1924 and needed a lot of work. It was going to be a warehouse. The first two [artists]I recorded there were Little Hatch and Jimmie Lee [Robinson]. We were recording Jimmie Lee. Little Hatch was there visiting [from Kansas City] and we had tape and we finished Jimmie Lee. So, we sat Hatch in front of the mic in '98. We were just rolling. I remember, when I first got to Salina, I'd still go to bars. It's the way I knew to entertain myself. So, when I went to Kansas City. I went to the Grand Emporium. There was this little old Black dude playing the blues. I'm like, 'Man, he's really good. This guy needs to be recorded'. |

|

| At the time, I was barely selling records. I didn't even have a dream to be in the music business much less the recording business. And, to think a few years later that I was the first one to do a studio record on Hatch! It blows my mind. It means a lot to me. And, I did it because I should do it. I wanted to do it. When it comes to recording the blues, I loved Hatch and his music and I thought it should be recorded. The money will happen if it's supposed to. I did it for the right reasons. I wanted it documented. People needed to hear how good this son of a gun was. I like all kinds of music. I don't like really hard metal. I don't really like new country and I don't really like rap. I listen to classical at home. It sounds so good on my stereo. I had a childhood friend who [ended up] playing with C.J. Chenier. When I went back to Lafayette, I called him. I said, 'I been recording blues. I'm learning more and more about Louisiana music'. He said, 'Let me tell you something. If you're into the blues, I'm going to send you a cassette of this guy who is in C.J.'s band. This guys the real deal, man'. I listened to it. The vocal was very distant like he was too far from the mic. But you could hear this raw, rough Howlin' Wolf kind of voice. That's all we had to go by. We were like, 'Man, that sounds pretty damn good'. So, we took a chance and we recorded him. He made enough for three records. Two more records are going to come soon out on HiRez downloads. When CBS [television] came here and did a piece, the reporter asked a great question. She said, 'I understand you love this blues music. What if the people out there don't buy it or they don't feel the same way about this music as you do? What are you going to do then'? [Laughs] I told her, 'Well you know what'? I'll just sit and listen to this stuff myself, then [laughs]. So, I bought a church [in Salina] originally for excess storage. My mother one day says, 'Well, this would make a great studio'. That's how that got implanted in my mind. Then we had Jimmy Rogers play in 1997 a few months before he died. [Construction] on the church wasn't finished yet. And, it was such a good turnout - me and Jimmy D. Lane [Jimmy Rogers' son] said, 'This was great, we have to do it again'. We named the church Blue Heaven in 1998. Joe Harley [producer for AudioQuest and a close friend] named it that. That year we recorded Weepin' Willie [Robinson]. He was 73 and nobody ever heard of him. Mighty Sam [McClain] and Susan Tedeschi came from Boston and recorded with him. That year was the first Blues Masters at the Crossroads. My aim was to get the best legends who had ties to the beginning of it all. Jimmy [D. Lane] played, and Jimmie Lee Robinson, Little Hatch, Snooky Pryor, Honeyboy Edwards, all those guys. This year will be our 18th year. A lot of people love it. I'm real happy to be able to get this music out that I've been wanting to get out - in a very high quality way to get out. I had asked Jimmy D. to help me record all these blues guys – my right hand man. He was the musical director. We recorded a lot of blues at the church. We have ten studio albums we hadn't released yet and they're going to come out on the HiRez – same with the concert. It's kind of unearthing something. There are three Honeyboy [Edwards], three Little Hatch, two Harry Hipolite, one Jimmie Lee, and one Henry Townsend. I just never put them out. They're fantastic sounding. I may eventually put them out on records. |

|

| Everything was a natural progression. It's still fun but it's a lot of work. Super HiRez is doing really well and it's a real good place for me to put out the concerts. We recorded all of them. Now, the thing that's really kicking is the pressing plant. The vinyl thing is really where I got started. The Super HiRez is cool because I'm able to share that blues stuff that I might never put out [on a record]. I bought thirteen new pressing [machines] this year. I'll probably have [a total of] 24 when I'm done. We're kind of limited to the room [in our building]. The pressing plant is already going 23 hours a day. Last year we pressed a million records. I'm still [getting to release blues]. I'm going to be doing some Lightnin' Hopkins. I already did Muddy Waters. I lease the masters and press them. I recorded Marquise Knox and the Campbell Brothers [not long ago]. I love vinyl. I love analogue. It touches your soul. We're trying to get blues people into audiophile and knowing there's good stuff [out there] and we're trying to get audiophiles into the blues. We bought a printing press to press our own [paper] labels. The next step is to cut and master our own stuff. It's all to do with music. It's all to make your music sound better. There's no easy money. But, a lot of people say they don't want to do their hobby for a living, but this is my hobby and I don't get tired of it."

|